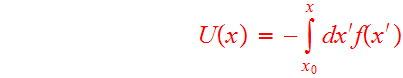

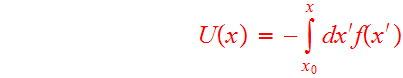

In a one-dimensional system it is always possible to define a potential energy corresponding to any given f(x); let

(1)

where ![]() is an arbitrary position at which

is an arbitrary position at which ![]() .

Different choices of

.

Different choices of ![]() produce potential energies differing by an additive constant; this

constant has no influence on the dynamics of the system.

produce potential energies differing by an additive constant; this

constant has no influence on the dynamics of the system.

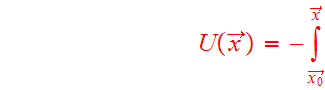

In a space of ![]() dimensions the analogous path integral,

dimensions the analogous path integral,

(2)

![]()

may depend on the exact route taken from point ![]() to

to ![]() ;

if it does, a unique potential energy cannot be defined. One condition

for this integral to be path-independent is that the integral of the

force f(x) around all closed paths vanishes. An equivalent condition is

that there is some function U(x) such that

;

if it does, a unique potential energy cannot be defined. One condition

for this integral to be path-independent is that the integral of the

force f(x) around all closed paths vanishes. An equivalent condition is

that there is some function U(x) such that

(3) ![]()

![]()

Force fields obeying these conditions are conservative. The

gravitational field of a stationary point mass is the simplest example

of a conservative field; the energy released in moving from ![]() to

to ![]() with

with ![]() is exactly equal to that consumed in moving back from

is exactly equal to that consumed in moving back from ![]() to

to ![]() .

.

In astrophysical applications it's natural to work with the

path integral of the acceleration rather than the force; this integral

is the potential energy per unit mass or gravitational potential, ![]() ,

and the potential energy of a test mass m is just

,

and the potential energy of a test mass m is just ![]() .

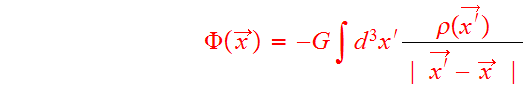

For an arbitrary mass density

.

For an arbitrary mass density ![]() ,

the potential is

,

the potential is

(4)

![]()

where ![]() is the gravitational constant and the integral is taken over all space.

Poisson's equation provides another way to express the relationship

between density and potential:

is the gravitational constant and the integral is taken over all space.

Poisson's equation provides another way to express the relationship

between density and potential:

(5) ![]()

![]()

![]()

Note that this relationship is linear; if ![]() generates

generates ![]() and

and ![]() generates

generates ![]() then

then ![]()

![]() generates

generates ![]() .

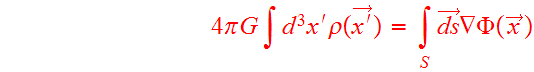

Gauss's theorem relates the mass within some volume V to the gradient

of the field on its surface:

.

Gauss's theorem relates the mass within some volume V to the gradient

of the field on its surface:

(6)

![]()

where the infinitesimal vector ![]() is an element of surface area with an outward-pointing normal vector.

is an element of surface area with an outward-pointing normal vector.

Consider a spherical shell of mass ![]() :

:

(a) the acceleration inside the shell vanishes

(b) and the acceleration outside the shell is

![]() .

.

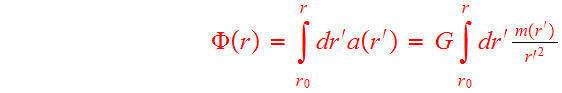

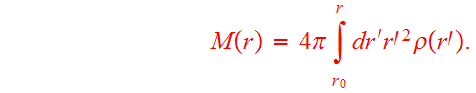

From these results, it follows that the potential of an arbitrary spherical mass distribution is

(7)

where the enclosed mass is

(8)

A point of mass ![]() :

:

(9) ![]()

This is known as a Keplerian potential since orbits in this

potential obey Kepler's three laws. If G=1 is set, the velocity of a circular orbit at

radius ![]() is

is ![]()

A uniform sphere of mass ![]() and radius

and radius ![]() :

:

(10a) ![]()

![]()

(10b) ![]()

![]()

where ![]()

![]() is the mass density. Outside the sphere the potential is Keplerian,

while inside it has the form of a parabola; both the potential and its

derivative are continuous at the surface of the sphere.

is the mass density. Outside the sphere the potential is Keplerian,

while inside it has the form of a parabola; both the potential and its

derivative are continuous at the surface of the sphere.

Galactic potential is the collective self-consisten field of

all stars within the galaxy. It is determined by the distribution

function ![]() which accounts for the mechanical state of the galaxy.

which accounts for the mechanical state of the galaxy.

Sun is located in our Milky Way which has ![]() visible stars and about

visible stars and about ![]() solar masses of gas

solar masses of gas ![]() with

with ![]() .

In comparison,

.

In comparison, ![]() .

Gas has little effect on main features of galactic dynamics.

.

Gas has little effect on main features of galactic dynamics.

Most of the stars in the galaxy travel on nearly circular

orbits in a thin disk whose radius is of the order of ![]()

![]() and thickness of the order of

and thickness of the order of ![]()

![]() with

with ![]() .

Typical circular speed of stars is of the order of

.

Typical circular speed of stars is of the order of ![]()

![]() and the time required to complete a galactic orbit at

and the time required to complete a galactic orbit at ![]() is about

is about ![]() .

The dispersion in velocities is about

.

The dispersion in velocities is about ![]() .

Age of the galaxy

.

Age of the galaxy ![]() .

Typical disk star (like our Sun) has completed over 30 revolutions.

Galaxy is in steady state. Why and how is explained by the steady state

solution of the distribution function

.

Typical disk star (like our Sun) has completed over 30 revolutions.

Galaxy is in steady state. Why and how is explained by the steady state

solution of the distribution function ![]() from the collisionless Boltzmann equation.

from the collisionless Boltzmann equation.

Consider first a practical choice on units for galaxy

collisions: ![]() The

gravitational constant is

The

gravitational constant is ![]() in cgs units. Typical galaxy size is measured in tens of kiloparsecs,

large scale structure of the universe is measured in Megaparsecs. Let

us determine the value of

in cgs units. Typical galaxy size is measured in tens of kiloparsecs,

large scale structure of the universe is measured in Megaparsecs. Let

us determine the value of ![]() in the new galactic units:

in the new galactic units:

(11) ![]()

![]()

![]()

This value of ![]() is an inconvenient value for

is an inconvenient value for ![]() to carry in simulations. Let us try galactic units which set

to carry in simulations. Let us try galactic units which set ![]() .

One possible illustration is

.

One possible illustration is ![]() In these units

In these units

(12) ![]()

![]()

![]()

In these units we can use ![]() in the simulations. With this choice two units are arbitrary, the third

unit is fixed. There is great flexibility to interpret simulation

results in physical units at the very end of the runs with

dimensionless numbers.

in the simulations. With this choice two units are arbitrary, the third

unit is fixed. There is great flexibility to interpret simulation

results in physical units at the very end of the runs with

dimensionless numbers.

![]()

![]() astronomy units

astronomy units

![]() Kepler orbits.

Kepler orbits.

![]()

![]() Kepler orbits (1

earth year)

Kepler orbits (1

earth year) ![]() one Saturn year

one Saturn year